Problem Setting

In our forthcoming paper on Annals of Applied Statistics, we propose a new method – which we call Bayesian Causal Forest with Instrumental Variable (BCF-IV) – to interpretably discover the subgroups with the largest or smallest causal effects in an instrumental variable setting.

These are many situations, ranging in complexity and importance, where one would like to estimate the causal effect of a defined intervention on a specific outcome. When the intervention is not randomized, researchers can recur to an instrumental variable (IV) to assess the causal effects. A valid instrument, \(Z\), is a variable that affects the receipt of the treatment, \(W\), without directly affecting the outcome, \(Y\). Using an IV enables researchers to effectively control for potential confounding factors and estimate the local effect of the treatment on individuals who would take a treatment if assigned to it, and not take it if not assigned (the so-called compliers).

If the classical four IV assumptions (monotonicity, exclusion restriction, unconfoundedness of the instrument, existence of compliers) hold, one can identify the causal effect of the treatment on the sub-population of compliers, the so-called Complier Average Causal Effect (CACE), that is: \[\begin{equation} \tau^{cace} = \frac{\mathbb{E}\left[Y_i\mid Z_i = 1\right]-\mathbb{E}\left[Y_i\mid Z_i = 0\right]}{\mathbb{E}\left[W_i\mid Z_i = 1\right]-\mathbb{E}\left[W_i\mid Z_i = 0\right]}={ITT\over\pi_C}, \end{equation}\] where the numerator represents the average effect of the instrument, also referred to as Intention-To-Treat (\(ITT\)) effect, and the denominator represents the overall proportion of units that comply with the treatment assignment, also referred to as proportion of compliers (\(\pi_C\)). For example, researchers can make use of an IV – such as being eligible for additional school funding – to isolate the causal effects of the primary treatment – i.e., receiving the funding – on the outcome of interest – i.e., the performance of students.

In IV settings, it may be of interest to disentangle the heterogeneity in the causal effects by estimating the causal effects within different subgroups. In our paper, we introduce and consider the following conditional version of CACE: \[\begin{equation} \tau^{cace}(x) = \frac{\mathbb{E}\left[Y_i\mid Z_i = 1, X_i=x\right]-\mathbb{E}\left[Y_i\mid Z_i = 0, X_i=x\right]}{\mathbb{E}\left[W_i\mid Z_i = 1, X_i=x\right]-\mathbb{E}\left[W_i\mid Z_i = 0, X_i=x\right]}= {ITT_Y(x)\over\pi_C(x)}. \end{equation}\] \(\tau^{cace}(x)\) is critical as it enables researchers to investigate the heterogeneity in causal effects within different subgroups defined by partitions \(x\) of the features’ space.

Methodology

Various causal machine learning methods have been proposed to estimate conditional causal effects. However, few methods have been developed to discover and estimate heterogeneity in IVs scenarios. To account for this shortcoming, we propose the BCF-IV method. BCF-IV is a three steps algorithm that can be used to interpretably discover the subgroups with the largest or smallest effects.

In step one, we divide the data into two subsamples: one to build the tree for the discovery of the heterogeneous effects (discover subsample: \(\mathcal{I}^{dis}\)) and another for making inference (inference subsample: \(\mathcal{I}^{inf}\)).

In step two, we discover the heterogeneity in the conditional CACE on \(\mathcal{I}^{dis}\) by modeling separately the conditional ITT (\(ITT_Y(x)\)) and the conditional proportion of compliers (\(\pi_C(x)\)). To do so, we adapt the Bayesian Causal Forest (BCF) method – proposed by Hanh et al. (2020), and recently featured on the YoungStats blog – for the estimation of \(ITT_Y(x)\), by including the IV, \(Z_i\), in functional form for the conditional expected value of the outcome: \[\begin{equation} \mathbb{E}[Y_i\mid Z_i=z, X_i=x] = \mu(\pi(x),x) + ITT_{Y}(x) z \end{equation}\] where \(\pi(x)\) is the propensity score for the IV: \[\begin{equation} \pi(x) = \mathbb{E}[Z_i=1\mid X_i=x]. \end{equation}\] Both functions \(\mu(\cdot)\) and \(ITT_Y(\cdot)\) are Bayesian Additive Regression Trees (Chipman, 2010) and are given independent priors to model differently the contributions of the covariates and the treatment on \(Y\). The conditional proportion of compliers can be expressed: \[\begin{equation} \mathbb{E}\left[W_i\mid Z_i = 1, X_i=x\right]-\mathbb{E}\left[W_i\mid Z_i = 0, X_i=x\right]=\delta(1,x)-\delta(0,x), \end{equation}\] where \(\delta(z,x)\) can be estimated using the Bayesian machine learning methodology for causal effects estimation proposed by Hill (2011). The conditional CACE can be computed as the ratio between conditional ITT and conditional proportion of compliers: \[\begin{equation} \hat{\tau}^{cace}(x) =\frac{\mu(\hat{\pi}(x), x) + \hat{ITT}_{Y}(x) z}{\hat{\delta}(1,x)-\hat{\delta}(0,x)}. \end{equation}\] One can then regress \(\hat{\tau}^{cace}(x)\) on \(x\) via a binary decision tree to discover, in an interpretable manner, the drivers of the heterogeneity (see, e.g., Lee et al., 2020).

In step three, once the heterogeneous subgroups are learned, one can estimate the conditional CACE, \(\hat{\tau}^{cace}(x)\) on the inference subsample \(\mathcal{I}^{inf}\). To do so, one can use the method of moments IV estimator from Angrist et al. (1996) within all the different sub-populations that were detected in the previous step. Alternative estimation strategies, such as Two-Stages-Least-Squares, can be employed as well. Finally, multiple hypotheses tests adjustments are performed to control for familywise error rate or – less stringently – for the false discovery rate.

Application

In our motivating application, implemented via the BCF-IV package, we evaluate the effects of the Equal Educational Opportunity program, promoted in Flanders (Belgium) to provide additional funding for secondary schools with a significant share of disadvantaged students. We use the quasi-randomized assignment of the funding as an IV to assess the effect of additional financial resources on students’ performance in compliant schools. The Flemish Ministry of Education provided us with data on student level characteristics and school level characteristics for the universe of pupils in the first stage of education in the school year 2010/2011 (135,682 students).

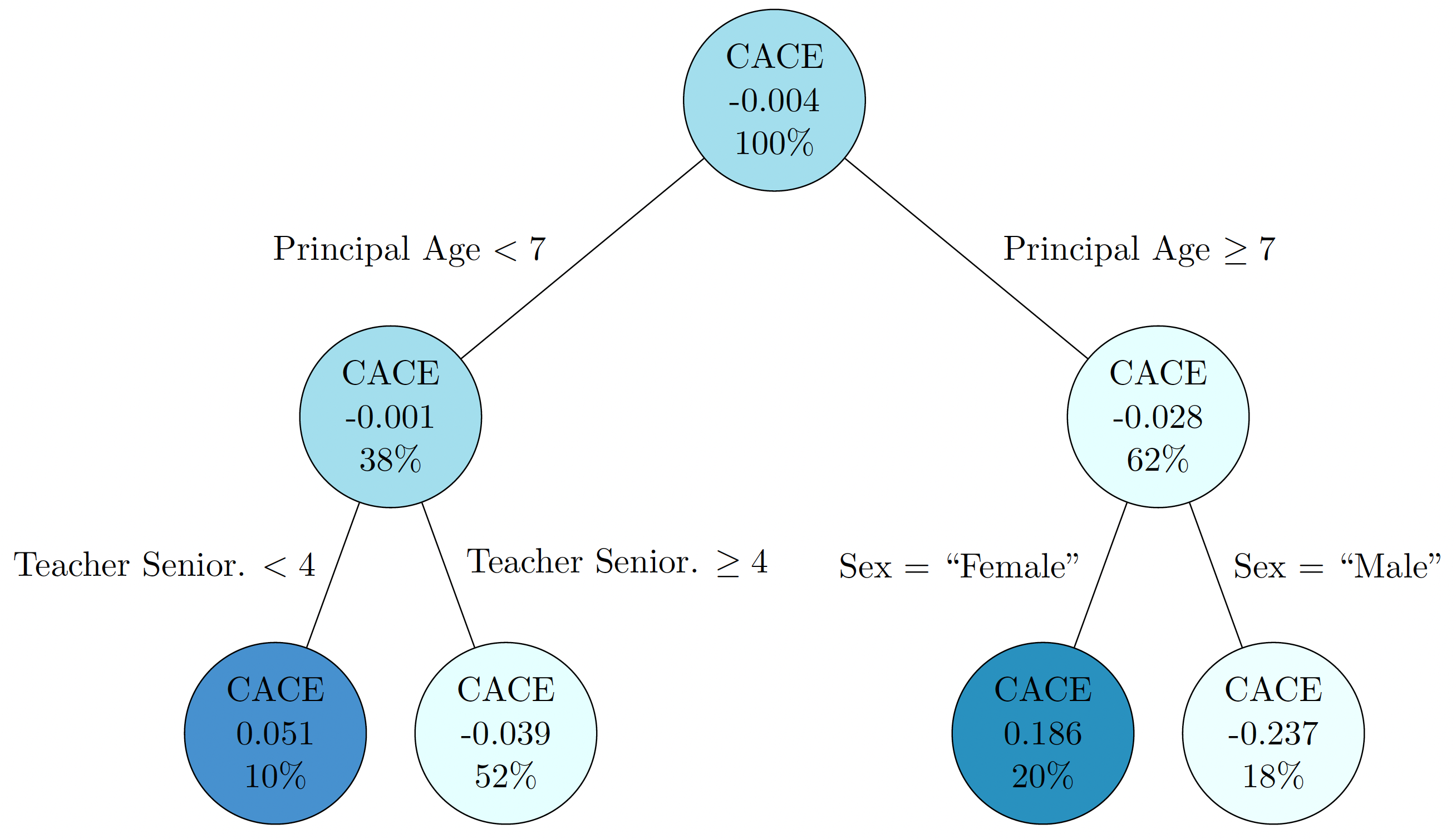

While the overall effects are negative but not significant (consistently with the findings of previous literature), there are significant differences among different sub-populations of students. Indeed, for students in schools with younger and less senior principals (i.e., principals younger than 55 years old and with less than 30 years of experience) the effects of the policy are larger (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Visualization of the heterogeneous Complier Average Causal Effects (CACE) of additional funding on student performance. The tree was discovered and estimated using the proposed BCF-IV model.

Conclusions

By investigating the heterogeneity in the causal effects, BCF-IV expedites targeted policies. In fact, BCF-IV can shed light on the heterogeneity of causal effects in IVs scenarios and, in turn, provides a relevant knowledge for designing targeted interventions. Furthermore, in a Monte Carlo simulation study, we manifested that the BCF-IV technique outperforms other machine learning techniques tailored for causal inference in precisely estimating the causal effects and converges to an optimal large sample performance in identifying the subgroups with heterogeneous effects.

Essential bibliography

This article is based on:

Angrist, J. D., Imbens, G. W., & Rubin, D. B. (1996). Identification of causal effects using instrumental variables. Journal of the American statistical Association, 91(434), 444-455.

Bargagli-Stoffi, F. J., De-Witte, K. and Gnecco, G. (2021+) Heterogeneous causal effects with imperfect compliance: a Bayesian machine learning approach. The Annals of Applied Statistics, forthcoming.

Chipman, H. A., George, E. I., & McCulloch, R. E. (2010). BART: Bayesian additive regression trees. The Annals of Applied Statistics, 4(1), 266-298.

Lee, K., Bargagli-Stoffi, F. J., & Dominici, F. (2020). Causal rule ensemble: Interpretable inference of heterogeneous treatment effects. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.09036.

Hahn, P. R., Murray, J. S., & Carvalho, C. M. (2020). Bayesian regression tree models for causal inference: Regularization, confounding, and heterogeneous effects. Bayesian Analysis, 15(3), 965-1056.

Hill, J. L. (2011). Bayesian nonparametric modeling for causal inference. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 20(1), 217-240.

.jpeg)