As a scientific community, we must understand how scientific collaboration (SC) works on both the individual and organizational levels to be able to propose R&D policies that are efficient. Unfortunately, the interdependent nature of SC among different levels is often not well considered in empirical studies. To address this issue, we will present the scientometric approach that provides a simultaneous insight into SC patterns on both levels: among researchers (individual level) and organizations (organizational level).

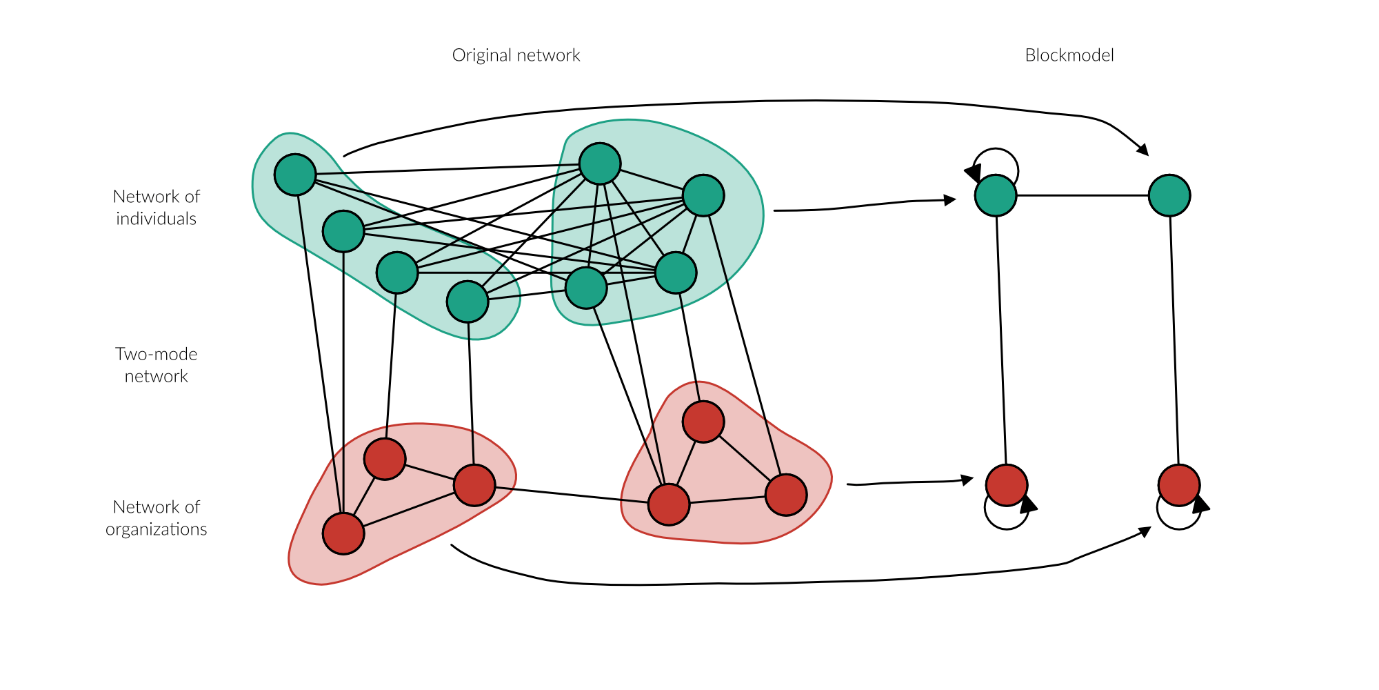

The approach is based on the social network methodology that represents SC with a two-level network (the example is shown in Figure 1). The nodes on an individual level refer to researchers while nodes on an organizational level refers to organizations. Researchers are linked if they wrote a scientific paper together while organizations are linked if they worked together on a research project. A link between a given researcher and a given organization exists if the researcher was employed by this organization.

Figure 1 Example of a two-level network (left) and the corresponding blockmodel (right)

By using a blockmodeling approach for such two-level networks, we are able to identify clusters of researchers and clusters of organizations that have similar SC patterns (see Figure 1). Experts in social network analysis would typically blockmodel (i.e., search for groups of nodes with a similar pattern of links to others) each network level separately and then combine the results. Instead, we used the k-means-based blockmodeling approach for linked networks (developed by Aleš Žiberna) that enables the two network levels to be blockmodeled at once and to thereby examine the interdependencies between the network levels.

In our study, we focused on SC in the field of social sciences in Slovenia between 2006 and 2015. We obtained data from the national information systems (SICRISS and COBISS) on 788 researchers and their research papers (3,367 research papers) and corresponding research organizations (64 distinct organizations).

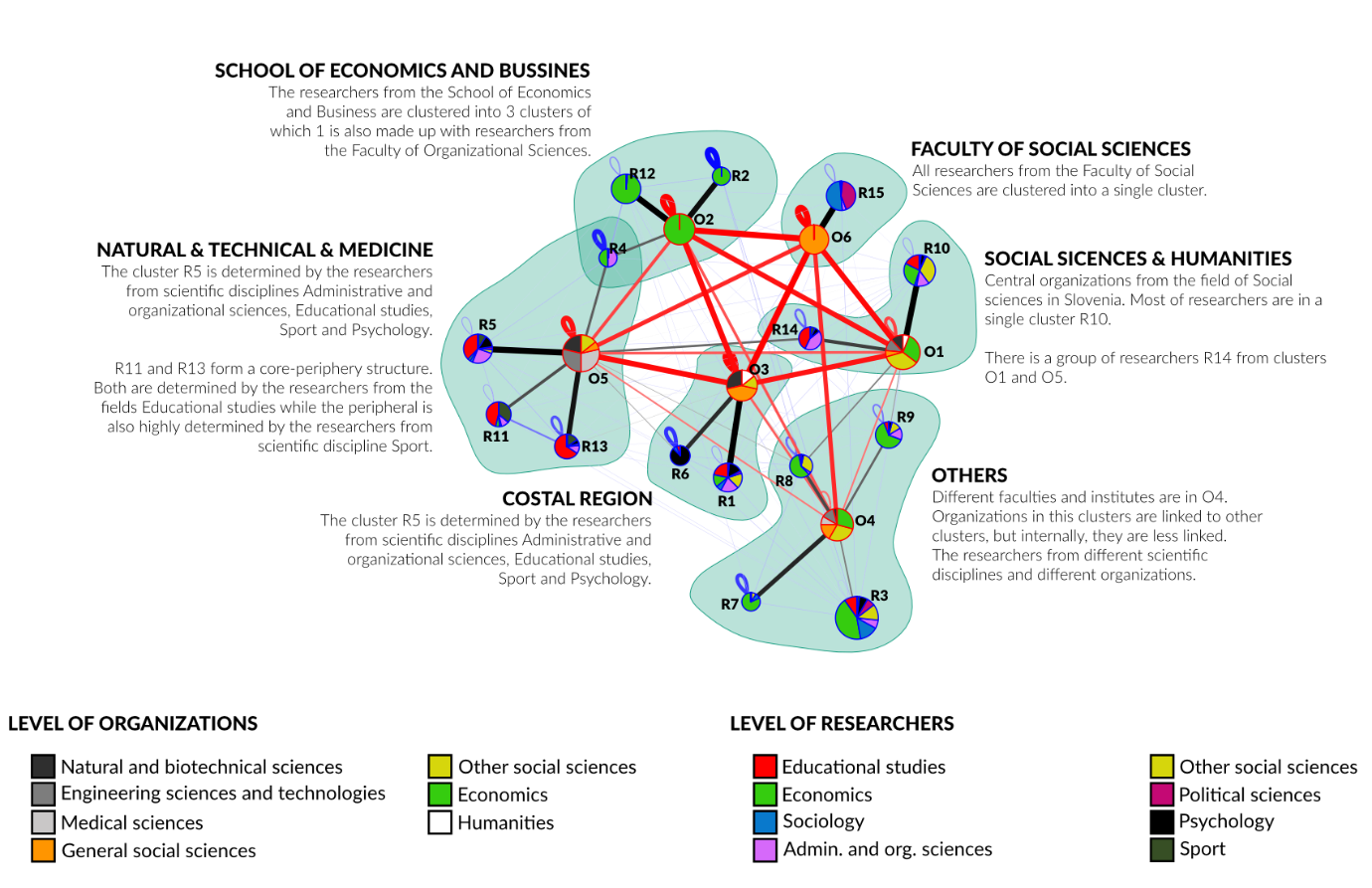

We applied the mentioned blockmodeling approach to the empirical network and obtained a network with 15 clusters of researchers and 6 clusters of organizations. The network of clusters (i.e. blockmodel) is visualized in Figure 2.

We can see the global network structure of researchers consists of many internally linked groups of researchers (the loops visualize this). Meanwhile, the clusters of organizations are not only well-linked internally, but also with each other. Focusing on the links among groups of researchers and groups of organizations, only a few links can be seen among the clusters of researchers who are employed by clusters of organizations that are otherwise linked. The absence of such links suggests that SC between organizations is generally not manifested in publications being written together by researchers from these organizations, indicating that the formal incentives to encourage SC between researchers from different organizations might not be seen in SC on the individual level. Instead, researchers’ organizational affiliations strongly determine their SC. Yet, since we can see that the clusters on both levels are very diverse in terms of scientific discipline, this means there is still a high level of interdisciplinary SC.

Figure 2 The obtained empirical blockmodel with certain interesting parts identified. Nodes with a blue-colored border (marked with the letter R) denote groups of researchers, whereas nodes with a red-colored border denote groups of organizations (marked with the letter O). Organizational node sizes are in proportion to the total number of researchers from organizations belonging to a given cluster. The size of nodes for individuals is in proportion to the number of researchers in each cluster. The widths and color-intensity of the edges within individuals and within organizations are in proportion to the density of the blocks connecting two given clusters of individuals or organizations. The widths and color-intensity of the edges between clusters of individuals and clusters of organizations are arranged so as to show the share of individuals from a given cluster of individuals who are affiliated with a given cluster of organizations. The legend shows the corresponding scientific disciplines.

Now, let us focus on individual parts of the blockmodel that is

obtained:

Now, let us focus on individual parts of the blockmodel that is

obtained:

-

Two clusters (clusters O2 and O6) of organizations with only one organization in each (i.e., School of Economics and Business, University of Ljubljana and Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana) can be identified. While all researchers from the Faculty of Social Sciences are found in a single cluster, researchers from the School of Economics and Business are in three distinct clusters that feature a low level of SC among them.

-

The other central organizations in the field of Social sciences in Slovenia are gathered in a single cluster (O1). Some researchers from this cluster collaborate with researchers who belong to another cluster of organizations (cluster O5) from the scientific disciplines Administrative and organizational sciences, Educational studies, Sport, and Psychology.

-

A cluster of organizations geographically located in the coastal region of Slovenia or which run research activities in that region (cluster O3) is also visible.

-

The organizations in the last cluster (cluster O4) are different faculties and institutes. These organizations are less strongly linked to each other and the corresponding researchers come from different scientific disciplines.

Based on the above descriptions, we can identify certain factors that affect SC on the organizational level in Slovenia: the size of organizations (some organizations with a very high number of researchers are found in their own clusters), geographical position (e.g., particular clusters largely consist of organizations located entirely or partly in the coastal region of Slovenia), and type (some clusters consist of organizations whose primary activity is not research).

The main conclusion is that while Slovenian research institutions are strongly linked through co-participation in projects, these ties are not strongly reflected as co-authorships among groups of researchers who come from different institutions.

The results of our analysis are relevant in two respects. On one hand, they may be seen as an important step in the (methodological) analysis of the complex social networks that emerge through different forms of SC in modern science. We are living in times of the tremendous growth of various types of SC, which is changing the “image” of modern science. On the other hand, the results of our analysis are useful for stakeholders involved in R&D policy (especially in small countries like Slovenia). The times when R&D policy actors could act without attracting criticism have passed. Today’s R&D policy actors must draw on objective expertise (even if still rare in practice). Finally, conducting analysis like what was presented here could also help compensate for the lack of such objective expertise.

This article is based on:

Cugmas, M., Mali, F., & Žiberna, A. (2020). Scientific collaboration of researchers and organizations: a two-level blockmodeling approach. Scientometrics, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-020-03708-x

About the authors

Asist. Dr. Marjan Cugmas, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, marjan.cugmas@fdv.uni-lj.si

Prof. Dr. Franc Mali, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, franc.mali@fdv.uni-lj.si

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Aleš Žiberna, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia, ales.ziberna@fdv.uni-lj.si